Taking Care of Business: Sustainable Engagement with OCW and OER

Taking Care of Business: Sustainable Engagement with OCW and OER

John Casey, Hywell Davies, Chris Follows, Nancy Turner, Ed Webb-Ingall, University of the Arts London, Centre for Learning & Teaching in Art & Design, 272 High Holborn, London, WC1V 7EY

j.casey@arts.ac.uk, h.w.davies@csm.arts.ac.uk, c.follows@wimbledon.arts.ac.uk, nancy.turner@arts.ac.uk, e.webb-ingall@chelsea.arts.ac.uk

Copyright: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 UK: England & Wales License.

Abstract

Involvement with OCW/OER creation and the Open Education community is seen as an optional extra in our institutions, carried out by enthusiasts, often supported with short term external funding. As an activity it remains at the margins, making the transition to long-term sustainability a major challenge. This situation has been aggravated by the recent and ongoing global financial crisis and the resulting government austerity measures, which has led educational institutions in the UK to plan large cuts to their budgets. How can a continuing, or even increasing, involvement with OER activity be justified in such a climate of economic retrenchment? This paper advances a radical case for institutional engagement with OER and the associated communities as a good business opportunity to help reconfigure our institutions for a changing world educational market.

Introduction

This paper takes the form of a reflective interim report from the ALTO project describing the experience of a project team at the University of the Arts London (UAL) taking on the challenge of making the case for engagement with OER at both an institutional level and to individual academics. The ALTO project (Arts Learning and Teaching Online) at the UAL is a classic example of a short externally funded OER project, being part of a national UK initiative (JISC 2011) to establish an open collection of learning resources. From a government policy perspective there are a number of explicit incentives for this initiative, which include marketing the UK Higher Education sector to the world and improving the efficiency and quality of the production of digital learning resources in the university sector.

To promote involvement with the project the ALTO team examined a range of possible motivations from the perspectives of both individual academics and institutional management. What has been striking to us is the strength of the institutional 'business' case that has emerged from our discussions; best described as a kind of 'enlightened self interest'.

This paper describes how the ALTO project has developed and pursued the institutional business case for involvement with OER and related communities. It describes the journey that the project team has taken to address this aim and some of the emerging outcomes, which may also be of use elsewhere. It includes a discussion of how approaches to sustainable engagement with OER creation may, in turn, help support institutional and cultural change in the more effective delivery of the traditional education offered by universities.

Cultural Change Questions

The ALTO project at the University of the Arts London had as one of its high level aims to link engagement with OER to a process of educational culture change across the institution. Early on in the project discussions we decided to focus on the 'why?' question in relation to OER creation and sharing, with the hope that everything else would make sense from there. This became known as what we referred to as the 'philosophical' phase of the project where we entered into some quite intense discussion. Along the way the team sought answer to these tricky questions:

- Whose culture?

- What kind changes?

- Why change?

- How to change?

Who's Culture?

What became clearer in our discussion was that the culture we were talking about was not just that of teaching staff, important as that is, but potentially of many other parts of the university including senior management, central technical services and support staff. The use of creative commons licences needed senior management buy-in and, as described below, challenges some of the assumptions about the value of digital learning content that have been developed over recent years by UK policy elites. In this connection we found ourselves also having to dig down into some fundamental educational philosophical questions about the role of resources in learning. As a result we developed an argument (which became part of the project 'pitch' or 'spiel') that while learning resources were of course important the real 'value' was in the processes associated with the use of those resources. These processes were primarily associated with the work of human teachers and their interaction with the students but they also included more ephemeral things like student interactions, curriculum design, institutional infrastructure, culture and traditions and 'brand' etc. This approach was received well by both teachers and managers and also helped to allay fears that the project was somehow aligned with a crude technical determinist attempt to automate teaching.

What Kind of Change?

The question of what kind of change was, and is, a much more difficult proposition. The case of video recording lectures nicely illustrates this. In a fascinating institutional strategy e-learning meeting the suggestion of using pre-recorded lectures to release staff time to have more contact with students was tabled. The educational rationale for this is well understood and is perhaps expressed best by Dianna Laurillard (2002) who questions why such a 'medieval information transmission tool' still holds such a dominant position in higher education. But, it quickly became clear that while this is acceptable for distance learning institutions like the Open University it had serious problems in an institution like the UAL. This is because teachers of practice-based subjects such as Art and Design tend to see the full attendance, face-to-face teaching model as traditionally the only, and the best, way to teach. In such a traditional teaching culture extending the range of 'formal' study modes and options presents a real challenge. Paradoxically, in some ways, there was also strong interest in installing 'lecture capture' systems that would allow students to see lectures they had missed or to view them again for exam revision purposes. The real problem here was the proposition of replacing lectures with pre-recorded ones, again, the educational rationale is well understood - not all lectures are uniformly good or inspiring, recording and editing provides an opportunity to add illustrative material and gives students the opportunity to chose the time and place of viewing etc. The reasons for this reluctance to replace lectures was that it could be perceived by students as a reduction in contact hours - which all national student survey results cite as leading complaint. This would also have implications for marketing of UAL courses if it were picked up wrongly by one of the university review and rating services.

Of course this situation is not just a UAL or British phenomenon. Loui Schmier (2011), a prolific educational blogger, humorously describes the results of the same tendency in the USA, where students and their parents demand traditional lectures because that is what 'proper' higher education is perceived to be, resulting in the pursuit of ever-bigger 'mega' lecture halls to cope with the burgeoning demand. It is one of the great ironies of the continuing commodification of UK education (where the cost of teaching is transferred from general social taxes to individual payment) that modernisation and reform of HE teaching becomes more difficult. It is tempting to try to 'design' change in these institutions, but as Friesen observes (2009) these institutions tend to change at a very slow rate - 'evolve' is the term he uses. As a result of these considerations, the conclusions we came to in ALTO was that we would not suggest or prescribe any particular changes to teaching practices as being part of the ALTO mission - apart from the open and free sharing of learning resources that teachers (or students) chose to share. On reflection this was a very wise move on our part and enabled us to be viewed as facilitating change rather than directing it. The metaphor we adopted was that involvement in ALTO opens the door to cultural change, but what people do after they go through the doorway remains up to them.

Why Change?

With the question of what type of change being tackled and put to one side, as described above, the question of 'why?' in some ways became much easier to deal with. In this section we describe and list some of the reasons for involvement with OER that we have developed and 'road-tested' with staff at the UAL. It would be tempting to portray this overall process in linear terms but, in reality, we progressed in a series of iterative loops through these questions, which, were also usefully informed by the practical work the project was engaged with, sometimes hitting both practical and conceptual dead ends and being forced to retrace our steps.

In common with the rest of the UK higher education sector, the UAL faces a future of rapidly declining public funding while at the same time there are increasing pressures to deliver flexible and blended learning opportunities to an increasingly diverse student population. But, for practice-based subjects such as Art and Design, extending the range of study modes and options presents a real challenge. It is clear that the traditional teaching model as well as a wide range of associated institutional support systems needs to change, the tricky question for institutions is how to do so in such harsh times? An even trickier and more fundamental question is why?

Educational technology and its many proponents have failed to deliver a breakthrough change, despite constant claims to be on the brink of doing so. A lack of attention to systemic and soft issues (such as tradition, structures and cultures) is often cited as some of the causes for this failure. So, how might engaging with OER be a part of a wider cultural change such as breaking the current hegemony of classroom and studio-based teaching and the wider reform of education?

From our point of view, it is precisely because involvement with OER raises such systemic and soft issues that make it such a potentially strong engine for change. The ALTO project has concluded that there are surprisingly strong managerial and educational reasons for involvement with OER and the associated communities around the world and we list these below:

1. Collaborative links with the national and international OER communities of practice

2. A showcase for individual students, staff and the UAL for; promotion, networking and student recruitment

3. Developing the staff skills base to extend blended and flexible learning opportunities at the UAL

4. Building an effective institutional knowledge, infrastructure and skills for managing, sharing and preserving digital content, including learning resources

5. Raises the institutional profile and builds a sense of shared identity and unity

6. Improves resource coverage for subjects

7. Improve cross college/disciplinary collaboration by engendering a culture of openness, transparency and integrity

8. Increased use of e-learning technologies

9. Building a growing and sustainable collection of learning resources

10. A part of the institutional 'memory', a form of knowledge capture and management

11. A way of harvesting and passing on subject knowledge and teaching expertise (knowledge management)

12. Develops policy (e.g. IPR & Employment)

13. Students making well-informed application choices, resulting in better retention and satisfaction rates

From the point of view of teaching staff and students we found that there were also very strong reasons to be involved. From the start we proposed that students could and should be able to contribute to the creation of OERs, one of the rationales for this being that students are often an underused resource in higher education.

1. Sharing good practice - A positive professional development activity that can help you think and reflect about your practice as teachers and also see how others have taught similar or related content/practices.

2. Staff and students have easy access to a wider range of more specific and relevant resources which they can customize to their own needs

3. Saves time and effort

4. Improved morale and self esteem for staff and students from feedback and recognition for their work (includes web metrics and other impact indicators)

5. Make links with others across the country and the world to create longer-term collaborations and partnerships

6. Makes innovation public

7. Encourages collaborative educational design skills amongst staff, which is essential to supporting the extension of flexible and blended learning in more sustainable ways

8. Part of your professional portfolio of published work both as a teacher and as an art and design practitioner

9. Improved legal knowledge

10. Enhanced digital media design skills

11. Better learning resources for your students

12. Helps to get the right 'mind set' to think about how to extend the range of study modes and options for your students

13. Create teaching and study aids to reduce the amount of repetitive tasks that you do

14. Maintain your online personal profile and reputation as a teacher and practitioner

15. A recruiting tool for your courses - students can 'window shop' to make more informed choices

16. Gain confidence in the use of e-learning methods and tools

17. Working with students to co-design learning resources is an educationally valuable and more sustainable way of creating learning resources

How to change?

The experience of the ALTO project suggests that developing, through discussion, relevant and contextualized rationales for the potential benefits for engagement with OER provides a strong foundation for involvement. As we have observed above, we think the activity of freely sharing and developing learning resources opens the door to wider types of cultural change without being prescriptive about what the types of change should be. We certainly seem to be tapping into a mood or zeitgeist in the academic community at the UAL (and elsewhere) that sees this kind of open sharing as a key element in academic practice and identity. Perhaps, this is partly in reaction to the push to marketise and privatise the higher education system currently underway in the UK.

In the background research we have been conducting in the early phase of the project we have discovered that there is a strong move (both in policy and practice) towards collaboration in the design of production OERs (UNESCO 2010). We have taken advantage of this valuable insight to move the centre of gravity of the project in this direction, as a result we have engaged in collaboration with external institutions to share the design, development and review of a series of OERs. Although still in the early stages, this is looking like a very promising development that should produce more useful OERs that will be also used by the partners and could also lead to other types of future collaboration. In an evaluation of the UK Open University OpenLearn initiative (Lane et al, 2009) it was found that the act of openly sharing learning resources led to external collaborative opportunities as well an internal predisposition to greater sharing and cooperation. The reasoning behind this is that collaboration and sharing with the external world can also break down internal barriers by making them seem pointless. A central 'official' place to share and store OERs like ALTO can also give an institutional endorsement to this cultural change. It is, perhaps, this aspect of engagement with OER that is most important - the capacity to reinvigorate our institutional cultures and open the door to the possibility of change.

In following this path we have also been informed by recent policy thinking from the international OER movement especially the Paris UNESCO 2010 Policy Forum (UNESCO 2010), which stresses the need to move away from a producer/consumer model towards collaboration in the production of OERs - especially between the developed and developing world. There are also good educational reasons for taking this approach, experience indicates that teachers in mainstream HE can find it difficult to use and adapt other's learning resources. There are a number of reasons for this, intimately connected to cultural and contextual issues, and a growing realization that developing 'learning design' skills of academic teachers is part of the solution and that this is also needed to support more flexible and blended learning.

In connection with facilitating the change process, the approach adopted by the ALTO project might provide some useful insights. The way the project has worked has seen the project manager and project workers going out and working with individuals and groups on the ground to help them share and reflect on their resources and practice (especially in the context of collaborative learning design) - this has a lot in common with ethnographical approaches to successful socio-technical systems development as advocated by Edith Mumford (1995) and Ettiene Wenger (1998). The ALTO team are providing valuable information from their 'fieldwork' and giving the central institutional educational development unit a unique insight into practice and conditions on the ground. The combination of an institutional OER design development and publishing system with attached 'fieldworkers' collaborating with front-line teachers while also working with a central educational development unit could provide a model for an economically sustainable means of enhancing educational development provision in HE in a time austerity. A challenge that many central institutional development and e-learning units face is access to practitioners. The fieldworker model provides an effective and economical model for improvement and change, with each fieldworker being trained in a variety of skills to carry out their functions such as; digital learning media design, instructional design and IPR evaluation.

"Without People You're Nothing": Technical, Philosophical and Affective Issues

The quote at the head of this section is from Joe Strummer, the musician and political activist in the documentary film 'The Future is Unwritten'.

Pioneering work about introducing technology into workplaces by Mumford (1995) and others has long since shown that successful innovation always has to address the contextual and social aspects of using the new technologies. This applies especially to HE organisational and teaching cultures, which can be notoriously resistant to change, with and without technology. Until recently in the UK work in the area of sharing and reusing learning resources has been dominated by technological concerns with interoperability standards, learning objects, metadata and the creation of specialist repository software - sometimes becoming an end in itself rather than linked to real users (Barker, 2010). There was a genuine belief that if this were done according to the technical specifications then everything else would work. But, things have not worked out as expected and Fini describes it this way:

"This way of interpreting e-learning is running into a crisis: the promised economic effectiveness of content re-use is often hard to demonstrate or it is limited to specific contexts, while a general feeling of discontent is arising. (Fini, 2007, p. 5)"

To understand this apparent impasse Friesen (2004a) and Friesen & Cressman (2006) helpfully point out there is a set of important political and economic sub-texts connected to the proposed uses of technical standards and technologies in education that still need to be explored. Neglecting such 'soft' issues is a major cause of the problems cited above by Fini (2007). While Harvey (2007) notes a prevailing belief in neo-liberal thinking that there can be a technological fix for any problem and that products and solutions are often developed for problems that do not yet exist. In education, one of the materializations of this tendency is in the proposition that interoperability standards and techniques developed in the military and aviation sectors can be adopted in the mainstream public education system (Friesen, 2004a). But, despite the large amounts of money spent by public bodies in this area, Friesen (2004b) notes that there has not been wide adoption. In retrospect it is not surprising that standards and approaches that developed in the last century and originating in the military and industrial sectors have not taken root in mainstream public education systems; here teaching and learning is, inevitably, a far more messy, less controlled and contingent enterprise. Wilson (2009), who has been involved closely in the standardization development process, reflects on this state of affairs and suggests that that there is a need for a more lightweight approach such as epitomized in web standards. Elsewhere, Hoel (2010) who has also been involved in developing educational interoperability standards is bleaker in his assessment stating "the interoperability standards in the LET [Learning Education and Training] domain failed miserably". Although the mood swings in the educational technology community can sometimes resemble those in the merchant banking community (from 'master of the universe' to deep despair) we need to remember that innovation is often a dialectical process and rarely proceeds in a straight line - especially once people are factored in. Casey and Greller (2007) provide a more sanguine longer-term view of these developments in interoperability standards and suggest that some of these technologies may yet be adopted in unanticipated ways.

The ALTO project started out by committing to acquire and install a repository software package 'EdShare', a variant of the popular research outputs repository 'Eprints' supplied by Southampton University (Southampton University, 2010). While this software had made great strides in improving usability and customization to include features of relevance to teachers it is still at heart a repository. Repository software is optimized for storage and management and operates using a library paradigm - which is great for that particular purpose, but is not so good at presenting or publishing information. The presentational limitations of repository software in general have become apparent in the context of ALTO and the Art and Design academic community, who traditionally place a high importance on 'look and feel' i.e. affective and usability issues. Similarly, in the world of OCW/OER the emphasis is much more on presentation, publication and communication. Hence the leading initiatives do not use canonical repository software e.g. MIT OCW (previously Microsoft Content Management, now Plone), OpenLearn (Moodle), Merlot (An database driven central web site and distributed web 'feeder' sites), IRISS (Drupal).

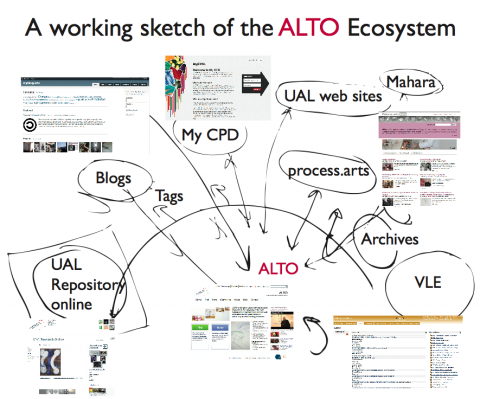

We realized that while repository software might be an essential component it would not be enough, we came to understand that ALTO would need to be more than just one software tool - it would need to be a system of connected and related tools. The repository software gave us a place to safely and reliably store resources in the long-term for which there was already a strong demand. But there was also a question of how ALTO might fit with other UAL information resources on the open web, which were quickly blossoming, often using Web 2.0 tools and services. We came to see that ALTO needed to fit into this wider and dynamic 'ecosystem' of online resources and associated communities. Two things became clear. First, was that resources in the repository would need to be easily 'surfaced' in other contexts in the wider UAL information ecosphere (not too hard technically) and beyond, in a variety of social media to aid dissemination and impact. Second, that the other components of the UAL ecosystem might want to use the repository to deposit some of their outputs now that the possibility of a long term storage area was possible.

A good opportunity to explore this kind of connected systems approach became available through an existing initiative called Process.Arts which was the result of a staff teaching fellowship to produce "an open online resource showing day-to-day arts practice of staff and students at UAL" (Follows, 2011). This was set up to address the need for staff and students to display and discuss aspects of their practice as artists and designers by providing a collaborative space in a public installation of the Drupal content management system that included many common Web 2.0 features. This has been very successful in a short time, with users uploading images and videos and discussing each other's work, user numbers and interactions are high and growing with considerable interest from abroad. We realized that if the repository was the officially branded 'library' part of ALTO then UAL sites and communities such as Process.Arts would be the 'workshop' areas where knowledge and resources were created and shared. As a result a decision to develop a high-level technical architecture to help ALTO adapt to fit into the wider UAL information ecosphere has been accepted by the project board.

We think this is a good way forward for institutional OCW/OER initiatives and recognizes the crucial importance of a social layer around open educational resources. It's simply not enough to provide a mechanism of storage or retrieval (important as that is) - this social layer enables the important human factors of communication, collaboration, and participation that are needed for sustainable resource creation and sharing within community networks. The technical solutions provided should help not hinder these activities; the guiding design principle for these socio-technical systems should be that of the concepts of conviviality (Illich, 1973, Hardt & Negri 2009) and stewardship (Wenger et al, 2009).

Conclusions

Engagement with OCW/OER can make 'sense' in a number of different dimensions including the very important personal and affective domain of individual self-validation and identity. But what been most surprising in the course of the ALTO project is that from a managerial and institutional perspective it also makes good business sense as a way of supporting the types of cultural change that are needed to develop and offer more blended and flexible learning opportunities and make well informed use of technology. For those senior managements that can see the opportunities, OER can be used as an effective strategic tool for change and collaborative external partnerships. This can in turn prepare educational institutions for an effective role in an international educational community that can also bring economic rewards. Rather than presenting involvement with OCW/OER as an optional extra, a kind of token 'good work' it makes sense to see it as key part of institutional strategy.

The argument for this way of looking things is forcefully made by Barbara Chow, Head of the Education Program at the Hewlett Foundation, In a paper entitled "Taking the Open Educational Resources (OER) Beyond the OER Community: Policy and Capacity" delivered at the UNESCO Policy forum in Paris Barbara Chow makes a persuasive case for the economic and pedagogical benefits of OCW/OER engagement.

When we look at involvement with OCW/OER from this kind of perspective and along the lines argued in this paper then the institutional and national 'value proposition' (to use Chow's phrase) for being involved becomes overwhelming even at the economic level. It does, however, require a shift in thinking and can be a challenge to existing the ideological belief systems after several decades of neo-liberal discourse from policy elites proposing economic competition between institutions as the main organising principle for Higher Education and conceptions of what a university should be (Barnett). Hartd and Negri suggest that such a mind shift is needed in order for society to move forwards and advocate what they describe as an 'entrepreneurship of the commons' in the sense of people being able to achieve their fullest potential without the constraint of such outmoded market constraints. The experience of the ALTO project seems to fit with these ideas and we are developing a number of creative options to sustain continuing engagement with OCW/OER at the UAL.

References

Barnett, R. (2003) Beyond all reason: living with ideology in the university. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Barker, P. (2010) http://blogs.cetis.ac.uk/philb/2010/09/10/open-closed-case/ accessed March 6 2011

Casey, J. Greller, W. (2007) The RDA of Standards for a Healthy e-Learning System. In Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society: The Italian e-Learning Association Journal, Vol. 3, n.2. http://je-lks.maieutiche.economia.unitn.it/index.php/Je-LKS_EN/issue/view/33 accessed March 6 2011

Chow, B. (2010) Taking the Open Educational Resources (OER) Beyond the OER Community: Policy and Capacity. UNESCO Policy Forum, Paris. http://oerworkshop.weebly.com/policy- forum.html accessed March 6 2011

Fini, A. (2007). Editorial, Focus on E-Learning 2.0. In Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society: The Italian e-Learning Association Journal, Vol. 3, n.2 http://je-lks.maieutiche.economia.unitn.it/index.php/Je-LKS_EN/issue/view/33 accessed March 6 2011

Follows, C. (2011) Process.Arts. http://process.arts.ac.uk/ accessed March 6 2011

Friesen, N. (2009). Open Educational Resources: New Possibilities for Change and Sustainability. In the International Journal of Research in Open and Distance Learning Vol 10 No. 5. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/664/1388

Friesen, N. (2004a). Three Objections to Learning Objects and E-learning Standards. In: McGreal, R. (Ed.). Online Education Using Learning Objects. London: Routledge. pp. 59- 70.

Friesen, N. (2004b). The E-Learning Standardization Landscape. Canada: Cancore. Retrieved 11/12/09 from: http://www.cancore.ca/docs/intro_e-learning_standardization.html accessed March 6 2011

Hardt, M., Negri, A., (2010) Commonwealth, Harvard University Press

Harvey, D. (2007) A short history of neoliberalism Oxford, University Press

Hoel, T. (2010) http://hoel.nu/wordpress/?p=426 accessed March 6 2011

JISC (2011) Open educational resources programme - phase 2. http://www.jisc.ac.uk/oer accessed March 6 2011

Lane, A; McAndrew, Patrick and Santos, Andreia (2009). The networking effects of OER. In: 23rd ICDE World Conference 2009, 7-10 June 2009, The Netherlands.

Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking University Teaching. Abingdon: Routledge and Falmer

Mumford, E. (1995). Effective Systems Design and Requirements Analysis: The ETHICS Approach. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Schmier, L. (2011) Random Thoughts. http://therandomthoughts.edublogs.org/?s=mega

Wilson, S. (2009) IMS's three-pronged strategy, Retrieved 11/12/09 from http://eduspaces.net/scottw/weblog/698961.html accessed March 6 2011

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E., White, N., Smith J.D., (2009) Digital Habitats: stewarding technology for communities Portland.

License and Citation

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/. Please cite this work as: Casey, J. Davies, H. Follows, C. Turner, N. Webb-Ingall, E. (2011). Taking Care of Business: Sustainable Engagement with OCW and OER. In Proceedings of OpenCourseWare Consortium Global 2011: Celebrating 10 Years of OpenCourseWare. Cambridge, MA.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| ALTO-Taking-Care-of-BusinessV3-CC-BY.doc | 103 KB |

| ALTO poster 1.png | 175.65 KB |

| ALTO poster 2.png | 156.66 KB |

To the extent possible under law, processarts has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to this Work, Taking Care of Business: Sustainable Engagement with OCW and OER.